International Poetry Affairs

with Nizar Sartawi

Nizar Sartawi is a poet, translator and educator. He was born in Sarta, Palestine, in 1951. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in English Literature from the University of Jordan, Amman, and a Master’s degree in Human Resources Development from the University of Minnesota, the U.S. Sartawi is a member of the Jordanian Writers Association, General Union of Arab Writers, and Asian-African Writers Union. He has participated in poetry readings and festivals in Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Kosovo, and Palestine.

Sartawi’s first poetry collection, Between Two Eras, was published in Beirut, Lebanon in 2011. His translations include: The Prayers of the Nightingale (2013), poems by Indian poet Sarojini Naidu; Fragments of the Moon (2013), poems by Italian poet Mario Rigli; The Souls Dances in its Cradle (2015), poems by Danish poet Niels Hav; all three translated into Arabic; Contemporary Jordanian Poets, Volume I (2013); The Eyes of the Wind (2014), poems by Tunisian poet Fadhila Masaai; The Birth of a Poet(2015), poems by Lebanese poet Mohammad Ikbal Harb. He is currently working on a translation project, Arab Contemporary Poets Series.

Sartawi’s poems and translations have been anthologized and published in books, journals, and newspapers in Arab countries, the U.S., Australia, Indonesia, Italy, the Philippines, and India.

Poetry and Science Joined in Matrimony by Nizar Sartawi

One thing is certainly not true: that scientists have some greater insight into the workings of nature than poets.

- Roald Hoffmann

Both [Science and poetry] at their best, use metaphor and narrative to make unexpected connections.

Introduction

Poetry is poetry, and science is science, and never the twain shall meet. * This notion – that poetry and science are mutually exclusive – has been widely accepted without question by the majority of critics, linguists, poets, scientists, and probably most people interested in these two major fields. Apparently, few people would believe that the language of science could be used for poetry or vice versa. I. A. Richards (1893 – 1979), one of the most prominent critics of the twentieth century, elaborated on the subject in his renowned book, Principles of Literary Criticism (published in1924). Discussing the theory of language, Richards distinguished between two uses of language: the scientific use and the emotive use. When used for scientific activities, he expounded, language is factual; it requires accurate, undistorted references: there is no room for fiction. On the other hand, when language is used for emotive purposes, it does not require truth, clarity, or logical consequence. Attitudes are interconnected emotionally, without necessarily being based on logical relations or facts.

I

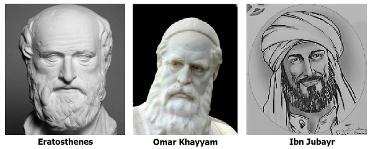

At its most extreme manifestation, the difference between poetry and science, has only divided the disciplines, but not the disciples. Notwithstanding their loyalty to the muses, a great number of poets throughout history, have been eminent scientists. For instance, the Greek poet Eratosthenes of the third century BC was a mathematician, geographer, astronomer, and music theorist; the eleventh century Persian poet Omar Khayyam was a polymath, mathematician, philosopher, and astronomer; and the twelfth century Andalusian poet Ibn Jubayr was a geographer and traveler.

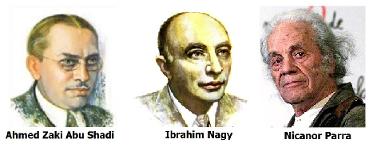

In modern times, a few scientists have become celebrated poets either locally or internationally, and most often their scientific career has been eclipsed by their poetic achievement. For example, the two Egyptian poets, Ahmed Zaki Abu Shadi and Ibrahim Nagy, who both died in the 1950s, were physicians, but in people’s minds they were and still are associated with the romantic movement in modern Arabic poetry. Likewise, the Chilean Nicanor Parra is celebrated in Latin America as an influential poet, not as a mathematician and physicist.

The division among the majority of these scientist-poets, or poet-scientists, basically lies within their personality. They tend to lead a dual life in which the poet is separated from the scientist – in which the poem has no connection with the profession. For instance, when a physician-poet treats patients, she or he is likely to think of their biological organs and systems in terms of function and dysfunction. But when they think of a person poetically, so to speak, they seem to experience a paradigm shift, where the focus is on other characteristics of that person, such as beauty, charisma, courage, wisdom, kindness, intelligence, influence, or even ugliness, stupidity, ruthlessness, and so on.

A few modern and contemporary poets, however, have demonstrated that poetry is not necessarily detached from science – that the poet (or the scientist) does not have to switch hats every time he or she crosses the border between poetry and science. In fact, the border for these poets often disappears entirely.

Of the many poet-scientists whose poetry shows that the two domains do not have to be apart, I have selected two world poets: Alberto Blanco from Mexico and Tze-Min Tsai from Taiwan. Both poets have successfully combined poetry and science in their poems. Or, to put it more precisely, they have treated scientific themes in their poetry. In the following sections I will talk about each of these poets and discuss two of his poems.

II

I was first introduced to Alberto Blanco in the spring of 2015 by a Jordanian poet who published her Arabic translation of one of his poems in an online paper where I publish many of my own works. The poet, who, like me, did not know Spanish, based her translation of the poem, titled “Quantum Theory,” on an English translation, which was also posted below her Arabic translation. I could immediately see how distorted her translation was. To explain the quantum theory, Blanco used simple examples to make his point:

To explain the quantum theory, Blanco used simple examples to make his point:

Radiated heat – in a camp fire

as well as in the atomic explosions at the center of the sun –

is not a continuous flow:

it's more like the beating of the heart

than the slow running of a river,

because radiation proceeds by quantum leaps.

Like a skillful teacher, Blanco provides a very simple example that every young girl or boy is familiar with, a camp fire. The camp fire, says he, radiates heat in the same way “the atomic explosions at the center of the sun” do. Blanco’s method introduces the unfamiliar through the familiar. He then provides two more familiar examples, the heart and the river to show the difference between quantum leaps, which happen at intervals (like heart beats), and continuous flow (like the river). The translator, who apparently failed to understand this simple, or rather simplified, notion, used her own interpretation, probably to make the poem sound more poetic, albeit deviating from the original meaning and losing track of the scientific argument.

I became curious to learn more about Blanco. I googled him, only to find myself bowing before a poet, scientist and prolific writer who has written more than seventy books and translated more than twenty, an essayist who has published hundreds of articles, a visual artist whose paintings and collage works have been displayed in exhibitions, a professor who has taught for a few years, a singer, a song writer, and much more. I was particularly intrigued by his poetry, especially when it touches on scientific subjects.

One of Blanco’s poems, “Theory of Relativity,” illustrates the poet’s capability of applying complicated scientific ideas to simple, everyday life experiences:

Problems aren't resolved,

they only occupy less and less space.

Problems are real, but they have limits.

Problems don't grow,

what grows is the consciousness of being,

one's vision.

Problems change shape constantly.

Vision does not; it always keeps

the same shape,

but it does change in size.

That's why it is correct to say

that only error changes,

as it is also certain

that vision is totally fluid

and that there's a terrible wind out there

and that its capacity for transformation is amazing.

In another poem, “Theory Of Uncertainty,” Blanco again takes a complex concept and explains it in the first part of the poem in simple language:

Heisenberg discovered

that a researcher

peering through a microscope

—whether realizing it or not—

is part of the experiment

that he is undertaking

because the same light

that he uses to observe

what is happening

in the experiment

fundamentally alters

the arrangement of what he sees.

To clarify Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle that precision is not possible because it has a fundamental limit connected with human interference, Blanco uses an example from behavioral psychology:

This is exactly what happens

when parents want to know

how their children behave

in the company of other children

when they are not there.

If the parents show up,

the form of interaction

changes immediately.

In the second part of the poem, Blanco takes Heisenberg’s uncertainty further, explaining how speed changes objects. A bullet train moving fast on the rails is different from a “train at rest” due the change in velocity. In the case of “atoms and subatomic particles” moving at a speed close to that of light, reality itself changes in a way that eludes common sense:

A train at rest is not the same

as a bullet train

gliding on the rails

at full speed.

This is evident.

Velocity changes

the conditions of an object.

When we speak of speeds

close to that of light

that rule and direct

the movements of the atoms

and the subatomic particles,

we are speaking of a separate reality:

An unthinkable world

where not only are

"objects” modified

—if the expression fits—

until they cease to be so,

but the same laws

that govern nature are others:

they have nothing to do with “common sense."

So, Heisenberg’s law of uncertainty

tells us that we cannot know

—from a subatomic particle—

its position or its velocity

at the same time:

if we know its velocity,

we do not know where it is and vice-versa.

In the last lines, Blanco suddenly shifts from the world of physics to the world of literature, suggesting that, in a sense, a poem is like subatomic particles: it eludes understanding because, unlike “immobile” critical writing, “it unfolds at high speed:”

The same thing happens in literature.

An immobile critique, an erudite essay,

a stagnant report is not the same …

as a poem

that unfolds at high speed

Poems are quick as quick can be …

We cannot know

—at once—

their form and their content.

And if we know the form of a poem

we will never know exactly

what it says.

Blanco shows how seemingly unrelated things are often governed by similar laws. But more significantly, he is responding to critics like Richards, suggesting that they are unqualified to judge poetry or to devise rules about how to use language for it. A similar message is also enclosed in the concluding lines of “Quantum Theory:”

Quantum theory proposes

–as opposed to classic mechanics–

that movement can exist

without a trajectory, without a journey, without an orbit.

At least without a known path,

and –what is more important–

without a path that can be known.

Is this not poetry?

Through the rhetorical question in the last line, Blanco sums up his views about poetry. Expanding on his comprehensive world view through physics, he invites us to recognize the beauty of this universe. At the same time, he wants to emphasize that, despite its complexity, or rather because of it, exploring the world of science can be a source of inspiration, and the scientific language can be used for poetic expression; it does not have to be presented or viewed as a dive in an ocean of cold facts.

III

The other poet, Tze-Min Tsai, is also a scientist who brings poetry and science together. An Associate Professor at the Asian University of Taiwan, Tsai, holds a PhD in Chemical Engineering and an MSc in Applied Mathematics. At the same time, he has a great passion for literature: He is not only a poet but also a novelist and essayist. Furthermore, he is a columnist for several poetry journals, director of Writers’ Capital International Foundation in Taiwan (Republic of China), director of Soflay International Asia, and English writer of BABEL MATRIX International Multilingual Literature Portal. His poetry has been translated into more than a dozen languages, and he has received numerous awards for his poetical and narrative works.

I have become acquainted with Tsai only recently: We were both selected as board members of the International Writers Association, Bogdani, in Brussels. And it was through this affiliation that I have had the opportunity to read his poetry.

From the beginning, I was convinced that here is another poet who has made compatibility between science and poetry not just possible but actual. Like Blanco, Tsai approaches scientific topics with the eye of a poet. Reading his poem “In The Dream, The Rainbow Does Not Sleep,” one may detect from the very beginning a dual state where two modes are simultaneously maintained: the poetic mode, expressed in the word “serenity,” and the scientific mode, clearly indicated by his reference to Einstein:

Time passes

Try to maintain the same lengths of the grid

Such serenity does not contradict Einstein's cognition

A mountain edge touches the sunset

Cold in the red-hot

Tsai undoubtedly is an astute observer of nature and natural phenomena. Combining observation with scientific knowledge, he is fascinated with how the forces of nature work together, constantly creating new phenomena, and shaping and reshaping them. Tsai’s dream poem goes on to explain how a rainbow is formed:

When the first light is covered

Driving the distant color clouds

Bringing down drizzle constantly

The light that penetrates the top corner of the window

Stretching at different angles of refraction

Arch bridge-like a rainbow

Call the colored dragon to ring

My window that never closed

Having described the phenomenon, the observer – the scientist – becomes a participant. Now the imagination is engaged, and the voice of the dreamer – the poet takes over. The scientist, however never loses sight of the experience:

Sitting on the dragon's dorsal fin

Tight scales protect me from pain

That silhouette soars up into the sky just like lightning

Just all of a sudden comes on the top of the rainbow

Smoothly

Such as Newton’s ideal world can’t find the friction

Only that fine silk clothing

Which

Makes every effort to shout in the air

In an attempt to prevent the falling down of the figure

With equal acceleration

To reach the terminal speed detached from the surface

The scientist and dreamer are both kept engaged in an implicit dialogue, the former reminding the latter of the laws of gravity, and the latter responding that this cannot stop him from dreaming.

When I fall in at the bottom of the clouds

Pray that gravitation will not forsake me

The quality is a very customary joke

Perhaps

Only let myself return to the dream again

Can no longer hear

Galileo's boast

Break through Aristotle’s defense with wisdom

The poet concludes with the crucial question:

Where can I find?

The illusion of literature

Where to find scientific endorsement

Thus Tsai gets at the heart of the matter – how to knit together poetry and science.

In “Internet Ranger” Tsai embarks on an internet journey in which he flies “Close to the speed of light/ Cruising in the boundless time and space.” He does not wish to visit war zones; he wants to “Enjoy the impact of the different aspects of human civilization.” He believes his desire can be gratified by visiting the house where Einstein lived, hoping that “… the theory of relativity and the mass-energy equations [would] soothe me silently/ Expect it to give a spiritual answer.” Next, he visits two great scientists, the seventeenth century French mathematician, Évariste Galois, and the Hungarian inventor Rubik Ernő. He then mentions Apollo 11, which landed on the moon in 1969. After that he pays a visit to Facebook, where his “… most enthusiastic friends in the above press so much “goods” again/ Forcing me to paste a poem…”

But is incapable of running away from the thoughts of war. On his way back from his scientist journey, he comes across a photo of the young boy who was found lying face-down on a Turkish beach in early September, 2015:

No way to ignore in return

That Syrian little boy sleeps on the beach

The small body was washed ashore only exposing half of the naive face

Which played how to face their own war

Weakness and sentimental whine flows in the body

Should I comfort him to sleep well?

Having concluded his internet adventure with this heart-rending experience, he decides to stop browsing the internet, apparently because he is appalled at the sight.

Ironically extremely

Maybe, should close the network then close my eyes

Learning to be a well-behaved mouse

Do not run around will be better

The internet poem is dream poem. But the dream turns at the end into a nightmare that brings sadness. It is significant that the poet decides to close the network and then close his eyes, thus concluding both the scientific expedition and the dream.

Conclusion

Robert Blanco and Tze-Min Tsai represent a relatively new trend in modern literature which challenges the theory that science and poetry by definition do not and cannot use language in the same way. Contrary to the notion that scientific language can only be used for purely scientific purposes, these poets have adapted it to their poetry.

Both Blanco and Tsai write poetry about scientific motifs. However, the two poets use partially approaches. Blanco’s poetry tends to progress methodologically: It usually starts with a complicated scientific concept, explains it using simple examples that are quite familiar to the reader, and eventually brings in literature, or poetry, to demonstrate that it too has features which are common with science. Tsai’s poem, on the hand, often takes the form a journey that occurs in a dream, or a trance, as he calls it in one of his poems. Science and literature are part of the dream, but like personae in all dreams, they appear, act, or move in a haphazard rather than systematic, linear, or planned manner.

Another remarkable difference is that in Blanco’s poetry, the poet positions himself outside the poem, where he can observe and explain. By contrast Tsai is directly involved in the poem, or journey, both as a dreamer and traveler who relates his own experience, not just his observations. Thus, while Blanco speaks of atoms and subatomic particles moving at a speed “close to that of light” (“Theory Of Uncertainty”), Tsai himself flies “Close to the speed of light” (“Internet Ranger”).

In his essay “In Defense of Poetry,” the English romantic poet Percy Bysshe made the distinction between “two classes of mental action, which are called reason and imagination.” Elaborating on the differences between them, Shelly concludes that “Reason is to imagination… as the body to the spirit.” Science of course belongs to the realm of reason, whereas literature belongs to the realm of imagination. Following Shelly’s logic, by joining science and poetry together, Blanco and Tsai unite the body with the spirit.

--------------------------------------

Note:

* This sentence is borrowed from by Rudyard Kipling’s famous poem “The Ballad of East and West” in which the first line goes: “OH, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.”

Zero Degrees of Separation

by Nizar Sartawi

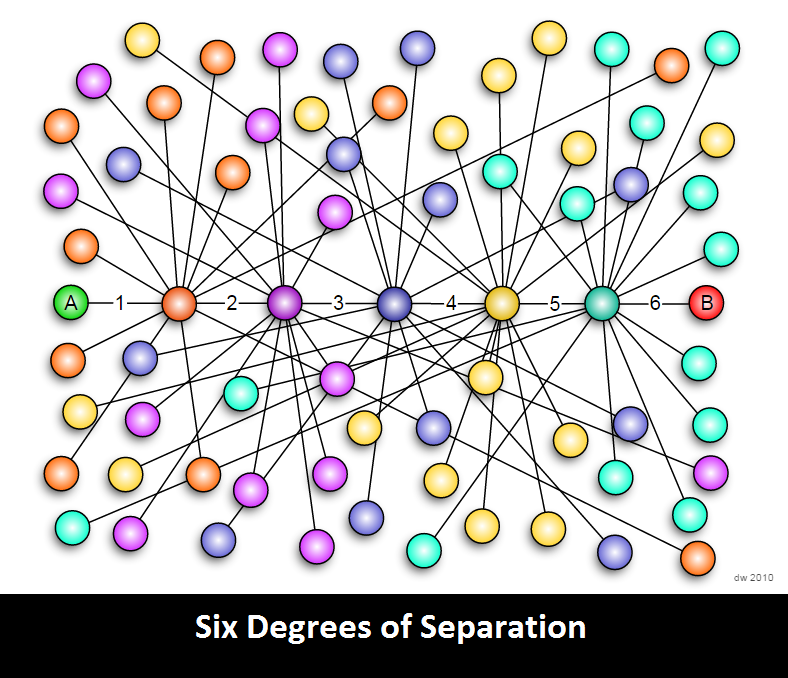

How close to, or distant from, each other are we… or can we be? According to the “Six Degrees of Separation” theory no two people in the world can be separated by more than six steps. How does that apply to different groups, like the Poetry Posse, for instance; or to people whom we meet in a conference or festival, for example, the poets who participated in the Rabat Poetry Festival last October? Are the degrees of separation among such groups or on such occasions reduced?

I

Last April, Samih Masaud, an economist and researcher who also dabbles with poetry, invited me to be a speaker at the launching ceremony of his newly published book, Haifa – Burqa, A Search For Roots, Vol. II. Samih’s Roots is a narrative work in which he traces back his lineage in Burqa, a village located within the governorate of Nablus in Palestine. He wanted to be acquainted, not only with the members of his “clan,” but also with the other clans of the village. That was not an easy task since many of the village inhabitants moved out of it and out of Palestine altogether as a result of the 1967 Arab-Israeli war. And yet Masaud managed to meet a large number of people, who told him their stories and also helped him contact other people who were connected directly or indirectly with Burqa. Very often he traveled to another town, or even another country to get in touch with these people. As a result of his indefatigable effort he has completed three volumes of his work, Volume One of which has recently been published by Inner Child Press.

In presenting Roots II, I explained that, consciously or unconsciously, Masaud used the “Six Degrees of Separation” theory. The six degrees concept was introduced by Hungarian writer Frigyes Karinthy in 1929 in his short story, “Chains.” In 1990 it was popularized by American playwright John Guare in a play bearing that name. It claimed that the distance of acquaintance between any two people in the world does not exceed six steps. For example, if your friend A has a friend, B, who has a friend, C, but B and C are not your friends, then you and B are separated by one degree, while you and C are separated by two. And if C and D are friends, but D is not your friend, then you are separated from D by three steps. On the other hand, you might be connected with D more directly through X, thus displacing the other degrees of separation.

To give a more tangible example, I can claim that the president of the U.S. and I are separated by no more than two degrees. How? I happen to know a few of the ex-members of the Jordanian cabinet and members of Jordanian parliament. These people know the king of Jordan, and the king knows the president of the U.S. (and of course a large number of rulers all over the world). Therefore, the Jordanian monarch and I are only separated by one degree, and the president of the U.S. and I by two.

This does not mean that the barriers of familiarity between us are removed. It is not as though I can go to the royal court in Amman, knock on the door and say: “Your Majesty, I am a friend of one of your friends; please allow me in as I have something to tell you;” or call the White House in Washington and say: “Mr President, I am a friend of your friend’s friend, and I want to know if we can have lunch together next Sunday!” And yet it is comforting to know that somehow there is an invisible thread there connecting all of us much more closely than we think since we are all members of this big club, Planet Earth, often called a small village, where the different types of layers separating people are becoming more porous, and can often be penetrated, or even removed.

II

The six degrees can be used for measuring the distance of relationships between people in a variety of situations. I have thought of it in connection with the Fourth International Poetry Festival held in Rabat last October.

A few months ago, Ahmed Taghi, a Moroccan poet, contacted me on Facebook and asked me to help him in organizing the festival. He knew about my friendship with a good number of poets from all over the world, and he wanted me to select and invite some of them to participate in the festival. He also wished me to translate a few poems and documents for the festival. I told him I would be glad to help.

On October 17, 2016 most poets who had confirmed their participation arrived in Rabat: Virginia Jasmin Pasalo from the Philippines broke away from another poetry festival she was attending in India and flew to Casa Blanca; Mauricio Gomes came all the way from Brazil; Margaret Saine and Peter S. William, Sr. from the U.S. had to cross the Atlantic before entering the Moroccan airspace, not realizing they were on the same flight; Italian poets Maria Palumbo and Mario Rigli flew over the Mediterranean; Abdulkadir Musa and Cascha arrived from Germany; Zulfa and I flew from Amman to Casa via Cairo; and Maria Victoria Bernal from Spain joined the group the following day.

We were all lodged in Bou Regreg Hotel, named after Bou Regrag River in Rabat. There we met Farouk Banjar and his wife from Saudi Arabia, Hassan Al-Matroushi from Oman, Mehdi Othman and Adulhakim Rubaiy from Tunisia, and a number of Moroccan poets.

Most of the poets coming from outside Morocco did not know each other; many were not even Facebook friends. As for me, I had only met two of them the year before: Bernal in Palestine and William in Kosovo. Mauricio, Maria Palumbo, and most of the Arab poets had not even been my friends or each other’s on FB; I don’t know how many steps of separation stood between us. At best, we were just virtual friends; seas or oceans stretched between us.

But it was not just that. There were at least two major barriers. The first was the language barrier: Only a few participants knew English, the most common language among the participants. The second was the cultural barrier: At least six cultures were represented in the festival: The European, North American, Latin American, Asian, North African, and Middle Eastern.

And yet these and other, less perceptible, barriers began to collapse when the poets met; we immediately began to connect. You could see us gathering in small or large groups in the hotel lobby, which was not very spacious, or the restaurant patio, after breakfast or in the evening. We talked, whispered, laughed; we took short and long walks; we dined together in restaurants, all sitting around a long table which we formed by bringing together five or six small tables; and we took photos, thousands and thousands of fabulous photos that featured the happy, smiling, faces.

During the next three days poetry readings were organized, but we also continued other informal group activities. Thus we found ourselves becoming so close you would think we had known each other for years. Everybody was becoming everybody’s buddy.

Finally the festival ended and each of us went back home. But we are still full of Morocco and of each other. Abdulkadir writes articles in German that we do not understand, so we use google translate. William is preparing a book combining poems about and photos from Morocco, like the one he did for Kosovo in 1915. And the poets have very interesting chats on FB and Messenger. We talk about Morocco, we talk about poetry, we tell jokes, we laugh, and we post photos. It is all done virtually, but one can sense how, in a very mysterious way, our communication is full of life, full of spirit.

III

How many degrees separate us now after Morocco? According to the six-degrees concept we are separated by ZERO degrees. But of course that does not say anything about the closeness of the relationship. It does not distinguish between a casual friend and a real one. It does not account for the degree of intimacy. A friend in this context simply could be an acquaintance – somebody you know… period.

Perhaps we need a less inadequate system to measure separation and non-separation more appropriately. Certainly, we all can think of individuals whom we know very well – a neighbor, a class-mate, a co-worker, a relative, … etc., i.e., individuals from whom we are not separated by others. And yet we could assert that for all practical purposes we are separated, not just by one or two or six degrees, not even a hundred or a thousand, but by an infinite number of degrees.

By the same token there are people who are ostensibly distant from us, but with whom we share thoughts and beliefs, opinions and attitudes, feelings and sympathies. These are the ones whom we hold so dearly, whose friendship we cherish, whose presence we appreciate and thank God for. They are the ones we love; they are our kindred souls.

Taro Aizu, Fukushima, and Gogyoshi by Nizar Sartawi

In my younger days I thought that the forms, or types, of poetry, such as sonnet, ode, ballad, epic, haiku, etc., have already been established and canonized, and that creating new forms rarely happens. Now I know better: There is no end to experimentation, creation, and creativity among poets: Simply put: imagination cannot be confined.

One new form that I learned about nearly four years ago is gogyoshi. Gogyoshi is a short poem written in five lines that has been introduced by the Japanese poet, Taro Aizu.* Unlike other Japanese traditional poetry forms, such as chōka, tanka, renga, haikai, renku, hokku, haiku and senryu, a gogyoshi poem does not follow any particular rules: it does not use rhyme, it has no specific number of syllables, the line length is free, and the poet does not adhere to any particular theme(s).

Taro, a native of Fukushima prefecture, has been writing gogyoshi for 12 years. But the world started to learn about this new form in 2012, when Taro, with the help of some friends, translated his book, My Fukushima into English and French. Today the book has been translated into more than 20 languages.

My Fukushima recounts the story of the people of Fukushima from the point of a view of a poet who is emotionally attached to the area: the land where he spent his childhood and adolescence and the people among whom he grew up. When the nuclear plant in Fukushima was struck by a great earthquake and exploded on March 11, 2011, Taro was living in Kanagawa prefecture, but he came home a few months later. Deeply shocked by the horrific effects of the disaster, he was inspired to write his poetry book.

* * * * *

My Fukushima comprises three parts: Gogyoshi, Gogyoshi Bun, and Haiku and Haibun. Most of the texts in the book are combined with pictures.

The first part, “Gogyoshi,” contains 25 gogyoshi poems depicting selected aspects of the natural life in Fukushima prior to the explosion. Taro begins with of a river:

The rising river

Flows with violence

In the spring light

From melting snow,

The distant mountains.

Then he goes on to describe scenes of the flora and fauna in Fukushima in a series of gogyoshi that induce us to partake of the joy of watching nature in its different manifestations: buds on a tree, Mongolia blossoms, a petal from a cherry blossom, orange blossoms, a ginko tree, wild monkeys, a sweet fish, a firefly, waterfall, the full moon and the snow. These scenes invite us to ponder how the various elements of nature exist together in beautiful harmony, for example, the sight of the rice fields at sunset:

A transparent ripple

Through the green, green

Rice fields

In a summer evening.

or a little girl giving the poet a leaf of a maple tree:

“My present!"

A little girl came running

And opened her palms

Holding a red fallen leaf:

A Japanese maple.

Taro concludes part I with two gogyoshi:

My dog on the lawn,

My cat on the table

My wife on the sofa,

All taking a nap

A beautiful Sunday.

~ ~ ~

Even though

Growing older,

I have a seed

To bloom someday

Deep in my heart.

In these gogyoshi Taro expresses his love of nature through his elaboration on its marvelous work. Apparently his purpose is to give us a glimpse of how he lived in peace and harmony with nature and the world before the nuclear explosion, preparing us for the big change after the disaster.

* * * * *

In the second part, entitled “gogyoshi bun,” Taro provides details about his visit to Fukushima in nine short chapters. Each chapter begins with a narrative, or story, and ends with a gogyoshi poem. We learn in the first chapter about “obon,” the Buddhist tradition which the Japanese practice in the summer: They go back to their native towns to pray for their ancestors. Because of the nuclear disaster and widespread pollution, Taro hesitates to go to his town at the beginning. But then he decides to go in August. When he arrives there he looks at the green rice fields stretching before his eyes. But he cannot imagine they are contaminated:

I can't believe

They are contaminated

By cesium winds,

These green, green,

Rice fields.

This brings to mind his earlier gogyoshi, prior to the explosion, about the “… green, green/ Rice fields” shaking like water waves against the gentle breeze.

In the second chapter he goes to his brother’s house and meets his nephews who, like all the children of Fukushima, wear dosimeters around their necks when they go out so that their teachers can check the radian level.

The dosimeters

Hanging from their necks

Even when the children

Play tag with me

In the green park.

In the next six chapters Taro selects examples of how life has changed dramatically in Fukushima, not only for people but the whole enviroment: A cat licks cesium rain; the poet eats a peach hoping the cesium will not give him cancer; a dairy farmer suffers because his cows drink contaminated water; beaches of a lake are almost deserted. In response to these tragic scenes, Taro shouts:

Come back,

Come back,

My former Fukushima

Where children used to play

Outside with their parents.

Yet, he never loses faith. When Fukushima starts to receive considerable amounts of medicine and donations from various parts of the world, the poet is relieved that “The people in Fukushima were not alone but had bonds with the Globe.” Filled with expectations, he closes the last chapter of Part II with an optimistic gogyoshi:

We'll sing a song

And dance again

Around the blossoms

In our hometown,

Fukushima, Fukushima.

* * * * *

It is this new tone of hope that distinguishes Part III, “Haiku and Haibun.” Part III partly resembles Part II in that both are prosimetric. Taro, however, replaces gogyoshi with haiku. This combination of prose and haiku producing 28 haibun texts.

Taro wrote Part III during the summer of the following year, after visiting several cities, towns and villages in the Fukushima prefecture. During his trips he is comforted to see how the environment is healing. Cesium is still in the air, but in smaller amounts; people are gradually returning to their previous life: growing rice, visiting the beaches and holding festivals.

Three visits seem to have a special value for Taro. The first is his visit to Miharu, a town located near the nuclear plant. Taro wanted to see “Takizakura,” a giant cherry tree claimed to be one thousand years old. Obviously Taro regards it as a symbol of the power of nature – its ability to survive disasters:

One thousand years

Flow through the blossoms…

Takizakura.

The second is his trip to the city of Minamisoma, to watch the horse festival called “Somanomaoi,” a tradition that the city people have had for about one thousand years – the same age as Takizakura.

Clouds of sand,

Neighing of horses…

Summer has come to Minamisoma!

The third is to Tokyo, where Taro joins a group of protesters, who stand in front the prime minister’s house for two hours to demonstrate against nuclear plants.

Humid night …

“No nuclear plants!”

I shout, I shout.

The last seven haibun end with prayers: the first three for a diary farmer’s family who fled to another prefecture, the fourth for the children of Fukushima, and the fifth for Takizakura – to live longer. The last two prayers are for the human race:

May genetic code

Not be polluted

By radiations.

~ ~ ~

May no living thing

Be extinguished by nuclear plants

Across the Globe !

* * * * *

My Fukushima is a chronicle that treats the worst tragic nuclear disaster since Chernobyl. By using gogyoshi, the form that Taro himself invented, along with haiku and haibun, two classical Japanese forms, which add variety and enrich the book, the poet has succeeded in inviting attention to both his work and his cause: the demand to abolish nuclear power worldwide. Taro’s achievement partly lies in the universality of his topic. The work is even more powerful because it combines prose with poetry and photography, thus becoming more interesting and mores memorable.

---------------------------------------------------

* taro Aizu and I have boon Facebook friends since early 2013. Taro sent me a soft copy of his Fukushima poetry book in January, 2013. He asked if I could translate it into Arabic. I managed to translate two of the three parts, and posted many of his gogyoshi in newspapers and on-line magazines.